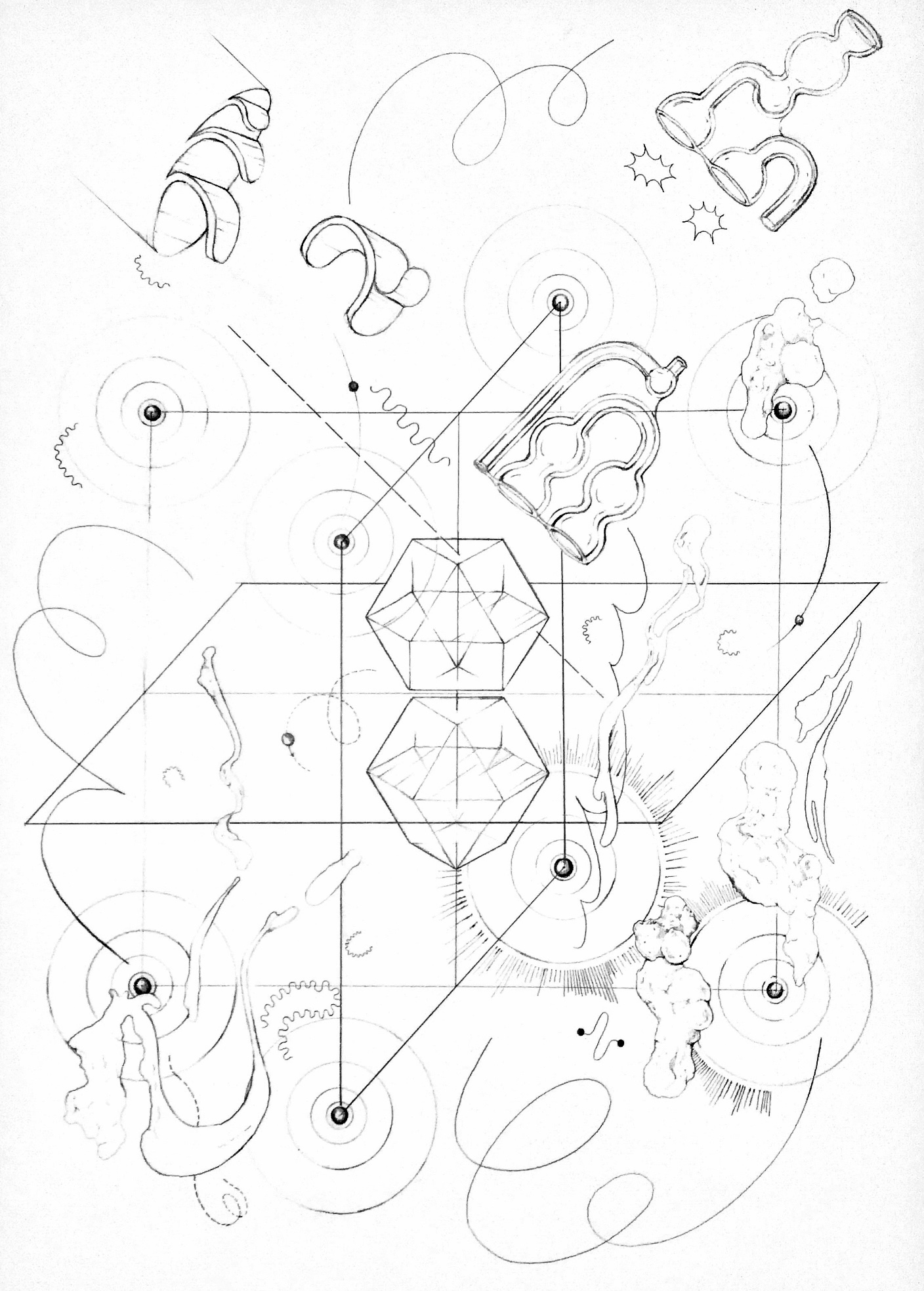

Phantoms as assemblage

Assemblage theory offers an approach to practice-based research that benefits from charting, mapping and exploring the extent of practice and how it is entangled with materials, processes, spaces, communities, people, ideas and objects. Thorughout my research I use drawing to chart the elements of my research in order to account for the complex, situated nature of practice-based research.

Scanning proved to be an artistically significant opportunity to probe scientific processes and use scientific practices to understand my phantoms via MRI. Phantom scanning at the Crick was possible thanks to the supervision, generosity and expertise of the head of MRI in vivo imaging, Dr Bernard Marshal Siow. It expanded the scope of my practice into other spaces and embedded it into scientific practices.

Interpersonally the lab was very welcoming and having the privilege of being able to access MRI at the Crick and Dr Siow’s extensive knowledge and experience provided an opportunity for me to work within the structures of scientific institutions. This enabled encounters with different ways of thinking about my work. Siow accepted my phantoms as scientific samples or specimens, attributing to them a kind of creatureliness and treating them as he would any other laboratory subject. Laboratory activities such as “labelling, marking, repeating, cleaning, numbering, noting, interpreting” (Law & Mol, 2001, p. 609) became part of my creative practice. Scanning verified that my decision-making process for phantom ingredients was consistent with the logic and processes of MRI. The machine read them as bodies, albeit unusual ones. Siow had to source new pieces of code had to help the scanner ‘see’ within them.

Assemblage theory offers an approach to practice-based research that benefits from charting, mapping and exploring the extent of practice and how it is entangled with materials, processes, spaces, communities, people, ideas and objects. Thorughout my research I use drawing to chart the elements of my research in order to account for the complex, situated nature of practice-based research.

Scanning proved to be an artistically significant opportunity to probe scientific processes and use scientific practices to understand my phantoms via MRI. Phantom scanning at the Crick was possible thanks to the supervision, generosity and expertise of the head of MRI in vivo imaging, Dr Bernard Marshal Siow. It expanded the scope of my practice into other spaces and embedded it into scientific practices.

Interpersonally the lab was very welcoming and having the privilege of being able to access MRI at the Crick and Dr Siow’s extensive knowledge and experience provided an opportunity for me to work within the structures of scientific institutions. This enabled encounters with different ways of thinking about my work. Siow accepted my phantoms as scientific samples or specimens, attributing to them a kind of creatureliness and treating them as he would any other laboratory subject. Laboratory activities such as “labelling, marking, repeating, cleaning, numbering, noting, interpreting” (Law & Mol, 2001, p. 609) became part of my creative practice. Scanning verified that my decision-making process for phantom ingredients was consistent with the logic and processes of MRI. The machine read them as bodies, albeit unusual ones. Siow had to source new pieces of code had to help the scanner ‘see’ within them.

Assemblage

![]()